Six years ago, I wrote Is GraphQL The Future? for the Artsy Engineering Blog. At the time, I thought it was possible devs might bypass REST and reach directly for GraphQL when designing APIs. We can now confidently say that the answer is “no”, but I’m still very proud of that piece, and I think I was right about a lot of other things.

I find myself revisiting GraphQL for the first time since working at Artsy, and the piece has been a useful refresher. I think I really nailed describing what GraphQL actually is, rather than analogizing it to things it has fundamental differences with.

So, what happened to GraphQL?

A healthy equilibrium

From my perspective, GraphQL neither faded away nor took over. A lot of people still use it and love it. It simply hasn’t supplanted REST as the default, and probably never will.

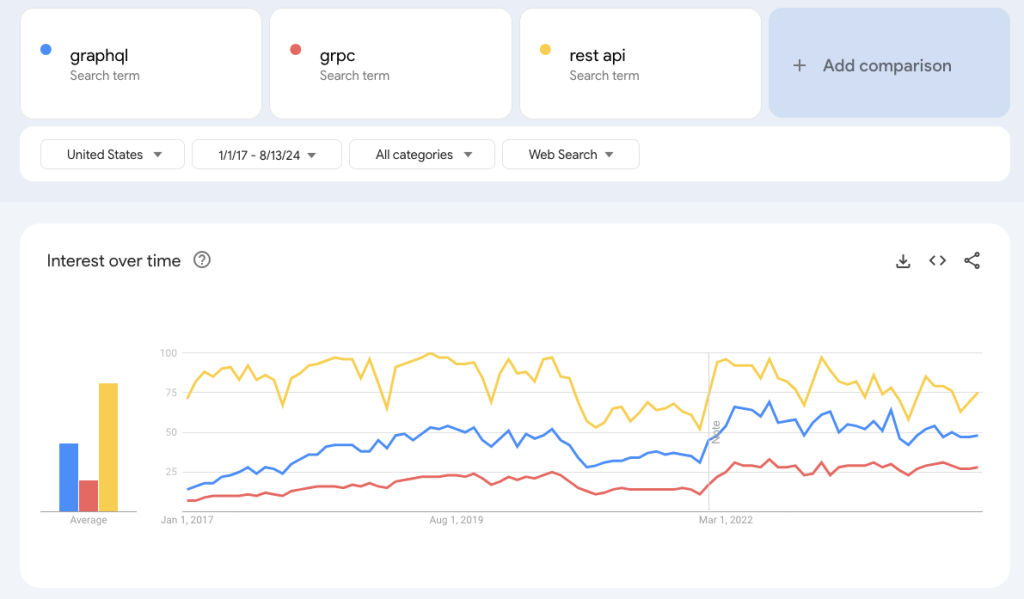

If Google Trends is a decent indicator, GraphQL was on a trajectory to overtake REST API, but it started to plateau around the end of 2019. gRPC, another post-REST API technology, also grew, but never to GraphQL’s peak.

GraphQL isn’t easy

The first reason GraphQL hasn’t taken over is that it’s more challenging to implement than a basic HTTP API. Notice that I don’t say REST API, because a truly RESTful API can take some thought and care. But when a new project is being started, it’s very simple to use an organically developed HTTP API.

GraphQL is deceptively pleasant to look at when it’s fully implemented, but there’s a lot of complexity on either side of the client-server interface. Writing resolvers to implement the server side takes some effort and tooling. And if the data needs of an app are interesting enough to merit GraphQL in the first place, a client-side library will probably be required. Lastly, optimizing a GraphQL API is complicated.

GraphQL isn’t high performance

When an application gets mature, if it’s performance critical, it often moves to a binary transport format, like gRPC. I haven’t used gRPC, but from a distance, it looks a lot like GraphQL, but with out the nesting. It also uses Protocol Buffers for its data serialization, which are higher performance than JSON serialization and designed with forward compatibilty as a design goal.

GraphQL isn’t ambitious

When I was working with GraphQL in 2017, it became pretty clear to me that its maintainers were not interested in it becoming the end-all, be-all of API technologies. They wanted the core technology to be excellent a small number of fundamental things. Anything that was possible within the core feature set did not merit features to create feel-good solutions, that might seem cleaner but would add complexity to every implementation and library. You can see this by browsing the GraphQL spec’s issue tracker.

GraphQL is great

All that said, GraphQL does still have its advantages. In a data rich application, where a screen may be divided into many data-driven widgets, each with parameters, GraphQL can be a great fit. Its fragments lend themselves to collocating the data needs of sections of UI with their UI components, and letting a library like Apollo handle the fetching and state management.

I also suspect it’s great for systems like CMSs, which have standardized data structures that can be used for a huge range of pieces of content.

Not everything is going to achieve the ubiquity of React, nor should that be the target. On the whole, I would call GraphQL a massive success.

Postscript

Back to the piece I wrote, I want to highlight one part I’m particularly proud of, which is the argument that GraphQL is a toolbox for making domain-specific scripting languages. If you’ve programmed professionally, it’s easy to get used to what a programming language is supposed to look like. We’re accustomed to vertically stacked lines of text representing sequences of operations within a lexical scope. We rarely question whether there are other ways to represent a computer program. There are! And I still think it’s fascinating that GraphQL created a unique representation, well suited to client-server communication, whether or not that was intentional. I am not aware of this perspective catching on, so this may forever remain a curiosity.

As I start to grapple with GraphQL again, I’m looking forward to seeing how the ecosystem has evolved.