For a few brief moments, my stock holdings in my former employer were hypothetically worth $5 million. This is the wild story of how I realized less than 1% of that value.

I’ll be pretty specific about some of the numbers, because equity compensation is a mystery to most people. Until I went through this, I never knew what’s possible and what’s normal. It’s a very complicated topic, but I hope that by sharing a real world situation, someone else might be able to learn something useful.

For nearly 3 years, I worked for an upstart mortgage lender called Better.com. I was hired to manage software engineers working on the core piece of technology we used for automating the extremely complex process of mortgage lending.

Better compensated us engineers well. The leadership of the company believed in paying aggressively to attract engineers who might otherwise work at the Googles and Ubers of the tech world. So, I got a pretty solid equity grant, on top of my salary: 75,000 stock options, at an exercise price of $0.80, vesting over 4 years.

(If you’re not familiar with how employee stock options work, the gist is that you get options as part of your compensation, but if you want to be able to sell your stock, you have to pay the company to exchange your option for a share, and then sell the share. The stock option locks your purchase price, no matter what the future value of the stock is. The reason for this is that it has major tax advantaged for the company and the employee, compared to compensating employees with stock, directly.)

Rocket ship 📈

I joined at just the right time. Interest rates were falling, which made it so that millions of people were in a position to refinance their mortgages. Better’s real invention, in my opinion, was technology that made it so that we could grow faster than any other mortgage company to meet that demand. And grow, we did. We were around 800 people at the time I joined the company. Two years later, we were over 11,000.

Our rapid growth into one of the country’s biggest mortgage lenders made us very attractive for investors, and our fundraising rounds valued us at increasingly lofty numbers. This culminated in a SPAC deal, backed by SoftBank, which valued the company at around $7 billion. At that valuation, each share of Better was worth roughly $27. Because my options gave me the right to buy shares at $0.80, this made my initial equity grant worth nearly $2 million, and I had vested about half of it at that time.

(Note that with 4 year vesting, I would need to stay at least that long to own all of my options.)

You might note that this is less than $5 million. We’ll get there.

SPAConomics

In the post-pandemic period, special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs) were a popular way to bring pre-profitable tech companies to public markets. The gist of it is that a group of investors will decide to create the SPAC and then take it public. The SPAC does not operate an actual business, it’s just a treasury of funds attached to a publicly traded company. Traditionally, each share is sold for $10 at the IPO, and that $10 goes directly into a bank account, and the money is not allowed to be spent on anything.

The operators of the SPAC then go out looking for a private company (called the target company) who is willing to merge. The private company gets all the cash the SPAC raised and inherits the publicly traded status of the SPAC, without going through a traditional IPO process, which is complex and expensive.

At the time of the SPAC IPO, the shareholders have no idea what company, if any, the SPAC will find to merge with. If it seems absurd that anyone would choose to write a blank check to invest in a SPAC IPO, there are a couple things that make it worthwhile:

- If the SPAC finds a company to merge with, the SPAC shareholders get a choice to keep their share in the combined company or to redeem their share for their $10 back, plus a small amount of interest. So the only real risk is the opportunity cost of the other places they could have invested their $10.

- The SPAC shareholders also get warrants with their shares, which are basically out-of-the-money stock options. If the company does well after the merger, these warrants will be worth real money.

Because of the redemption option, the target company doesn’t actually know how much money the SPAC is bringing to the deal. The full IPO proceeds is the maximum, but there is effectively no minimum. For this reason, another partner is often found who is willing to guarantee an investment if the merger succeeds (the merger is called a deSPAC). This partner is called a private investor in public equity (PIPE).

In Better’s case, the SPAC was called Aurora Acquisition Corp. (ticker: AURC) and our PIPE investor was SoftBank.

Rocket disaster 📉

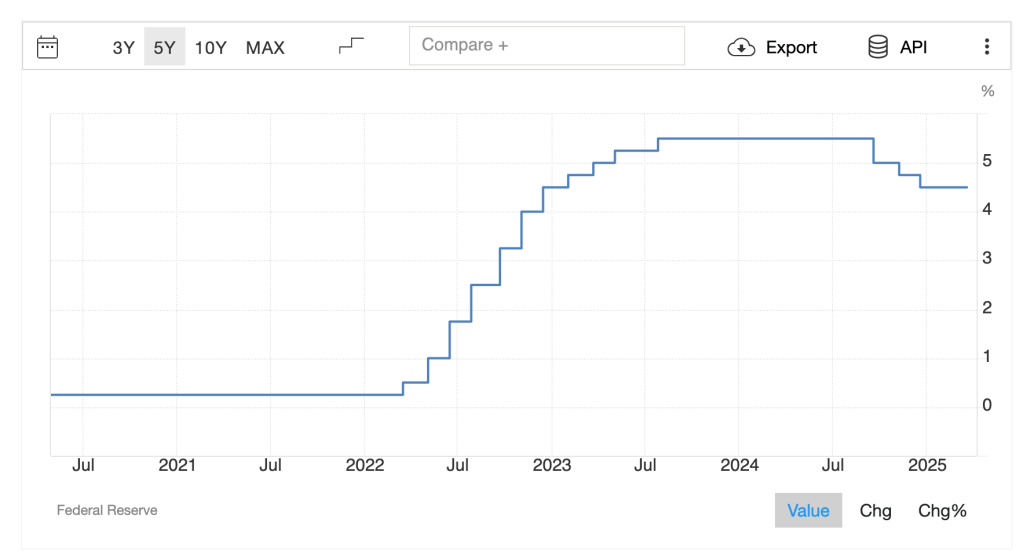

A lot has been written about the fall of Better, but the gist of it is that going into late 2021, it was clear that inflation was going to be a problem. The Fed raised interest rates, and that cause mortgage rates to go through the roof.

In my recollection, industry-wide refinance volume hit a brick wall a few months earlier, once rates stopped falling, as the number of borrowers in position to profitably refinance dried up. For a refinance boom to persist, rates can’t just stay low, they have to keep falling. So as rates found their bottom, around 3%, business slowed down. Refinance was Better’s bread and butter, at the time.

For reasons I’ll likely never be privy to, Better did not complete the deSPAC when times were good.

As 2022 proceeded, rates went through the roof and Better did waves of layoffs and buyouts. That June, I took a buyout offer. Back in the glory days, I had exercised some of the options I had vested, in order lock in favorable tax treatment, at a total cost of $22,000.

But just under 49% of the options I had earned were not exercised, and due to tax implications, I could not afford to. When you exercise options, it becomes a taxable event based on the value of those options at the time of exercise. The official valuation, which would have to be used for taxes, remained at $27, even though the the company was in freefall. I would have been taxed on over $668,000 of gains, even though it would have been impossible to sell my stock to cover the tax bill. 90 days after I left, I let more than half a million dollars of paper wealth vanish, because there was no way to convert it into actual wealth. Little did I know, things would get crazier.

Paper wealth

Months passed, and like most of Better’s employees, I moved on to the next thing. I had very little expectation I’d ever see any money for my stock. In mid-2023, the most absurd thing happened.

There are many mysteries to me of the story of Better, but one of the biggest is the fact that Aurora Acquistions never pulled out of the SPAC deal. They had locked in merger terms that valued Better at over $7 billion, but Better was clearly worth much, much less than that in 2022 and 2023. Yet, in mid-2023 (find link), Aurora’s management announced that they still wanted to do the deal. Most likely knowing that such an obviously bad deal would not play well to its shareholders, Aurora did something I’m not aware of any other SPAC doing: they allowed shareholders to redeem their shares before the shareholder vote to approve the merger. 92.6% of the shareholders chose to do so, reducing the amount of cash Aurora was bringing to the merger from $278 million down to a paltry $20.9 million, while also eliminating the vast majority of dissenters to the merger. But as before, SoftBank was providing the vast majority of the investment.

Because nearly all of the remaining stock was held by the Aurora insiders, a tiny number of shares AURC were actually available to trade. This situation allowed for manipulation of the stock price.

It was widely assumed that if the deSPAC actually did happen, the stock would plummet below $10, due to the deterioration of the business. This created an opportunity for short sellers, but in order to short sell a stock, a share must be borrowed. I don’t know exactly what was going on, but the stock price shot through the roof. On July 28, 2023, AURC hit its peak price of $62.91. The merger deal locked in a ratio of approximately 2.93 shares of AURC for each share of Better stock. This implied that my 31,444 shares were worth nearly $5.8 million.

Of course, if Better stock were tradable at that point, there would have been far more stock floating around to trade, and the run-up in the price of AURC could have never happened. Still, it was darkly amusing to have this much imaginary wealth.

The deSPAC

Incredibly, the deSPAC—the merger between Aurora Acquisition Corp and Better—did proceed. The weeks surrounding deSPAC day are deserving of their own story, but I’ll summarize here. After the merger happened, I ended up with 92,152 shares of the combined company. Of these, I sold 39,596 shares for a total of $44,613, which comes out to an average price of $1.13. Technically, these were shares of the same company that had once had a share price of $62.91.

The share price plummeted well below $1, and the company had to do a 1:50 reverse split to get its stock price back above $1, which is the stock exchange’s minimum price to remain listed. For months, the stock price hovered around $12.30, which is the equivalent of $0.25, pre-reverse split. It lost 97.5% of the value at the time the SPAC deal was agreed to. And that is less than 1% of the value it had when I was a paper multimillionaire.

But wait, there’s more

I thought there was a pretty good chance I would never be able to sell my remaining shares for the equivalent of $1.13 in the original pricing, which is $56.50 in post-reverse-split pricing. But I held my shares as a lottery ticket. My thinking was that eventually rates would come down in a downturn, and if Better still had an advantage in scaling their mortgage operations, they might be able to collect excess profits, and the market might reward the stock.

I would get my chance to sell, it turns out, but under much weirder circumstances.

On Sept 22, 2025, on the back of a tweet by one dude, Erik Jackson, the stock shot up to an intraday high of $94. I used to joke that Better should have picked the ticker DLFN to maximize its memestock potential. It seems it finally became one, anyway.

The tweet claims that Better is a fundamentally stronger mortgage company than a newer, flasher blockchain home loan company that went public a couple weeks ago. That company, Figure, IPO’d at a market price that values it at $7B—Better’s peak valuation.

I, unfortunately, missed the peak of that surge, but I sold 950 of my remaining 1051 shares for an average price of $60.14 ($1.20, in the original pricing), grossing me $57k. So I held for 2 years just to get pretty much the same price I did on day 1 🙃. But hey, can’t change the past, at this point, I’m lucky to get what I got.

Combined with the $44k I made on deSPAC Day, and subtracting the $22k I had to pay for my options, I netted about $79k for the equity I earned from working at Better for 3 years. Subtract some more for income taxes on my RSUs. Not the outcome you dream of, but that’s like a car’s worth of money.

I am still holding 101 shares. That’s a low enough number that I won’t be heartbroken if the stock craters again, and it’s too little to make crazy money if Erik Jackson is right. But knowing Better, there’s probably still drama to come.

Lessons

- The path to riches is narrow – Better was on top of the world. It seemed like a sure thing. So many things went right. But inability to complete the merger quickly, failure to prepare for economic changes, and one heinously conducted layoff destroyed 90% of the value.

- Take chips off the table – my one major regret from my Better experience is not selling more stock, sooner. While I could not have known that May 2023 would be the high water mark, I could have taken some gains by selling some stock on the private secondary market. A reasonable guess is that I could have gotten maybe $22 for my pre-merger shares, which would have netted me over $600k. I considered doing it at the time, but I thought, why pay some broker a giant fee, when I can simply wait until the deSPAC happens. The deSPAC would not happen for more than a year, well after the bottom had fallen out. I also should have sold more shares as soon as we went public.

- Don’t count your chickens – my family embarked on a massive renovation of our house at a time when it seemed like we were maybe weeks away from hundreds of thousands of dollars. The scale of the cost of the project was coming into focus in early 2022, just as my company was in free fall and it became likely I would never see a major pay day. We ended up going through with it, but it was a very different experience than if we had the money we had thought we would have.

- Have a plan – I could have made more money in the big bounce if I had set up standing orders to sell at different price points. The fact that I was still holing stock implies that I was waiting for a better opportunity to sell. But I never decided on my prices. It is possible I would have set those prices too low, but I think I probably would have set them higher on average than what I sold at.

- Be grateful – believe it or not, my overall experience at Better was incredible. I loved my work, I had incredible opportunities, and I got paid very well in cash salary. We also helped tons of households get into great mortgages. And as much as the stock didn’t work out to the best outcomes, the amount of money I was able to make in stock is still worth as much as I made in a year as a teacher.

Update (Oct 24, 2025)

I published this piece only a week ago, but BETR seems intent on upstaging me. Several days ago, the stock shot up again, triggering a standing sell order for 50 of my remaining 100 shares at $80. This morning, I sold a further 45 shares at $87.88. I do not regret selling my other shares at lower prices. There’s no way of knowing what will happen

I plan to hold the remaining 5 shares as an souvenir.

I did also want to share some very rough analysis. I asked Clause to compare loan volume to market cap for a number of publicly traded lenders. I have not double checked these numbers.

The lower the ratio, the better. That means each dollar of loan volume is worth more in stock price. Better is now approaching Rocket’s ratio, and Figure has a substantially lower ratio than everyone else. Figure used to be a mortgage company, but now only does home equity lines of credit (HELOCs). Better just announced that they are in the HELOC game this week, which probably accounts for the jump in stock price.